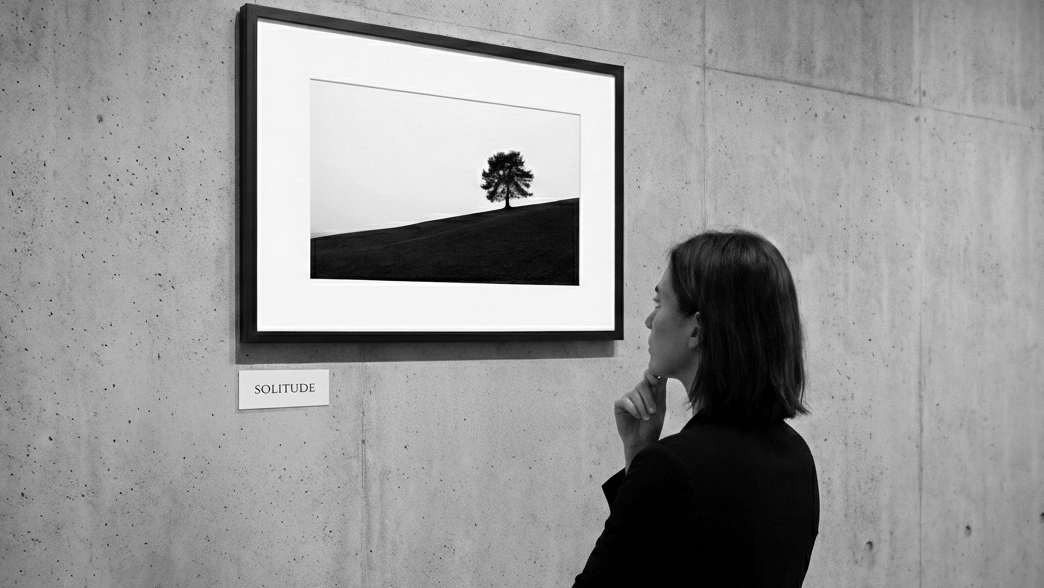

Still Life Is the Secret Training Ground for Better Monochrome Photography

There’s a strange thing that happens when photographers talk about still life. They either shrug it off as something boring or treat it like some kind of high art ritual that requires antique props, perfect light, and a studio full of gear. The truth sits somewhere in between. Still life photography is basically the quietest possible playground a monochrome photographer can ask for. It lets you slow down, control everything, and train your eye without the chaos of the real world getting in the way. And if you’re trying to get better at black and white, still life might secretly be the fastest way to level up.

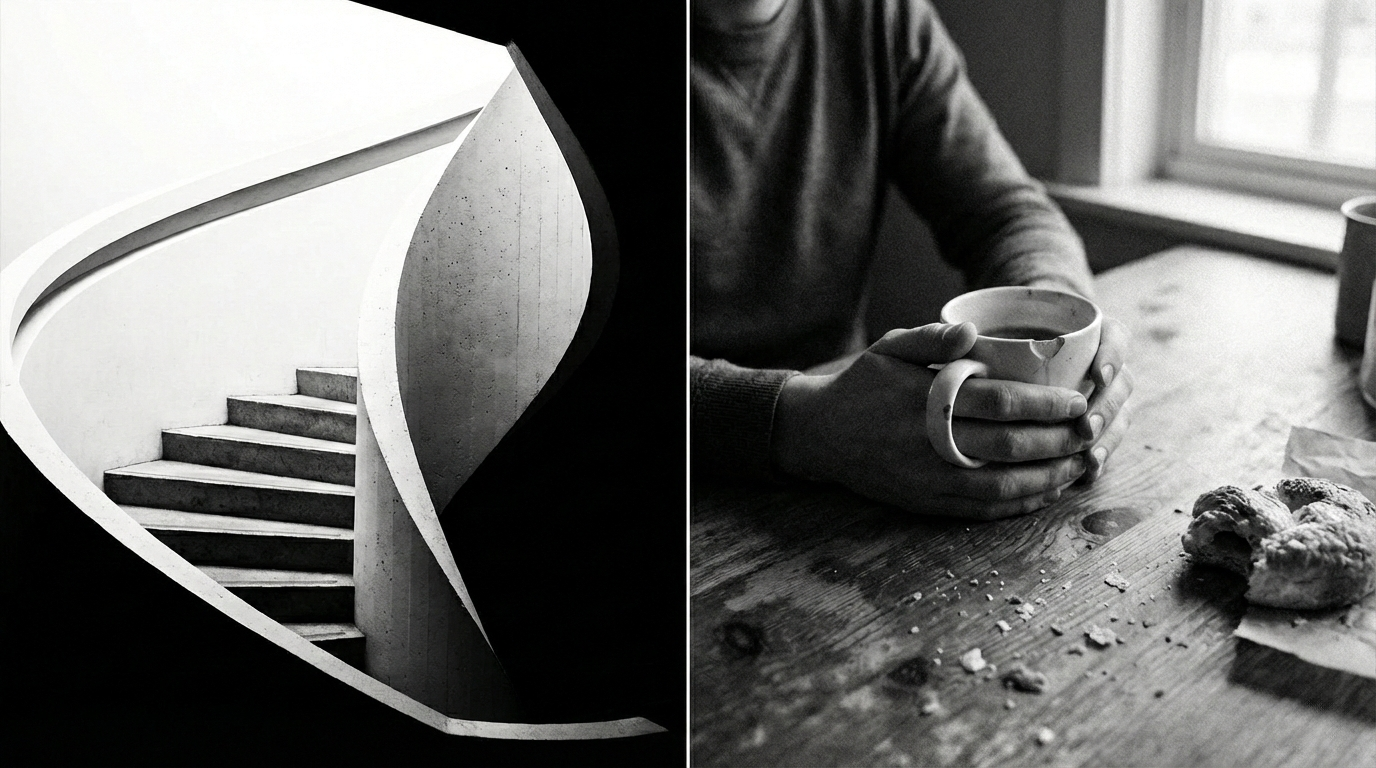

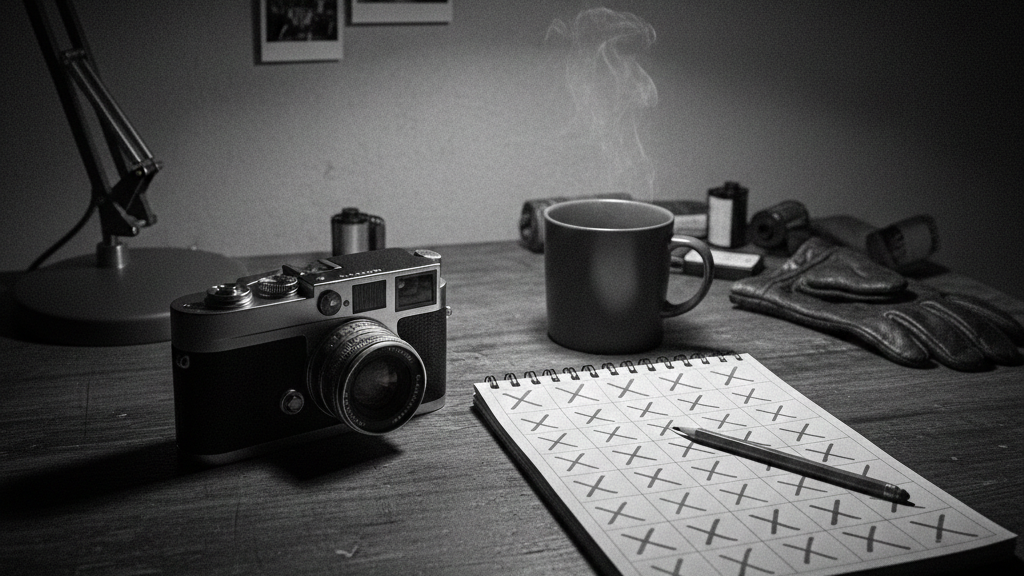

The reason is simple. Still life removes the variables you can’t control and forces you to pay attention to the ones you can. Light, shape, texture, negative space, tonal transitions — all the stuff that matters in monochrome becomes obvious when nothing is moving and nothing is competing for your attention. You’re not chasing the moment. You’re building it. Once you get used to arranging objects and sculpting light, you start to understand what actually creates visual impact. That awareness carries over into every other part of your photography, whether you’re out shooting on a busy street or trying to make sense of a complicated landscape.

Another benefit is that still life makes you think in terms of form instead of subject. In black and white, a glass bottle, a stack of books, or a piece of fruit isn’t interesting because of what it is. It’s interesting because of its shape and the way it interacts with light. When you start to look at simple objects this way, you stop relying on obvious subjects and start designing images. That mindset is huge if you want to develop a stronger personal style in monochrome.

Still life also teaches patience. It rewards small adjustments, tiny changes in angle, little shifts in light. You start to see how dramatically a shadow moves when the light bumps an inch to the left. You start noticing gradients that felt invisible before. When you go back to shooting in the real world, you’re suddenly more attentive. You react faster. You anticipate how light will behave because you’ve actually studied it in a controlled setting.

And maybe the biggest advantage: you can practice anytime. You don’t need a beautiful location or perfect weather or someone willing to stand in front of your lens. You can do this at your kitchen table with nothing but a window and a cheap object. Still life strips the excuses away, which is uncomfortable at first but incredibly freeing once you lean into it.

If you want your monochrome photography to feel more intentional, more refined, and more visually confident, still life is the training ground hiding in plain sight. It’s quiet work that produces loud improvements. And it teaches the thing that every monochrome photographer eventually needs to learn great black and white images aren’t found. They’re built.