Is Your Photography Too Clinical? The Problem With Digital Perfection

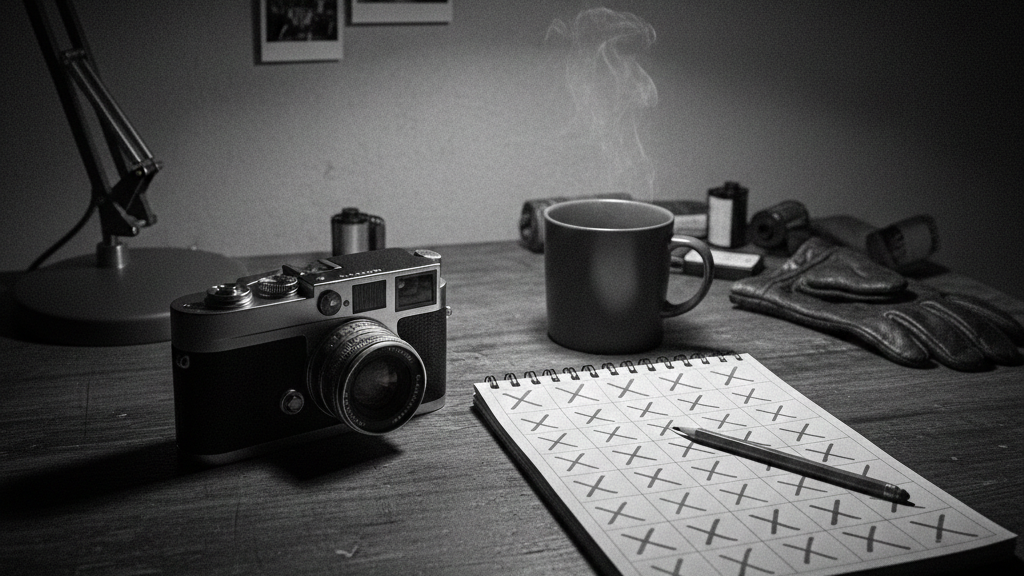

We live in an era of technical perfection. Modern digital sensors are miracles of engineering, capable of capturing incredible dynamic range and resolute sharpness with virtually zero noise at base ISO.

And for the monochrome photographer, that perfection is a problem.

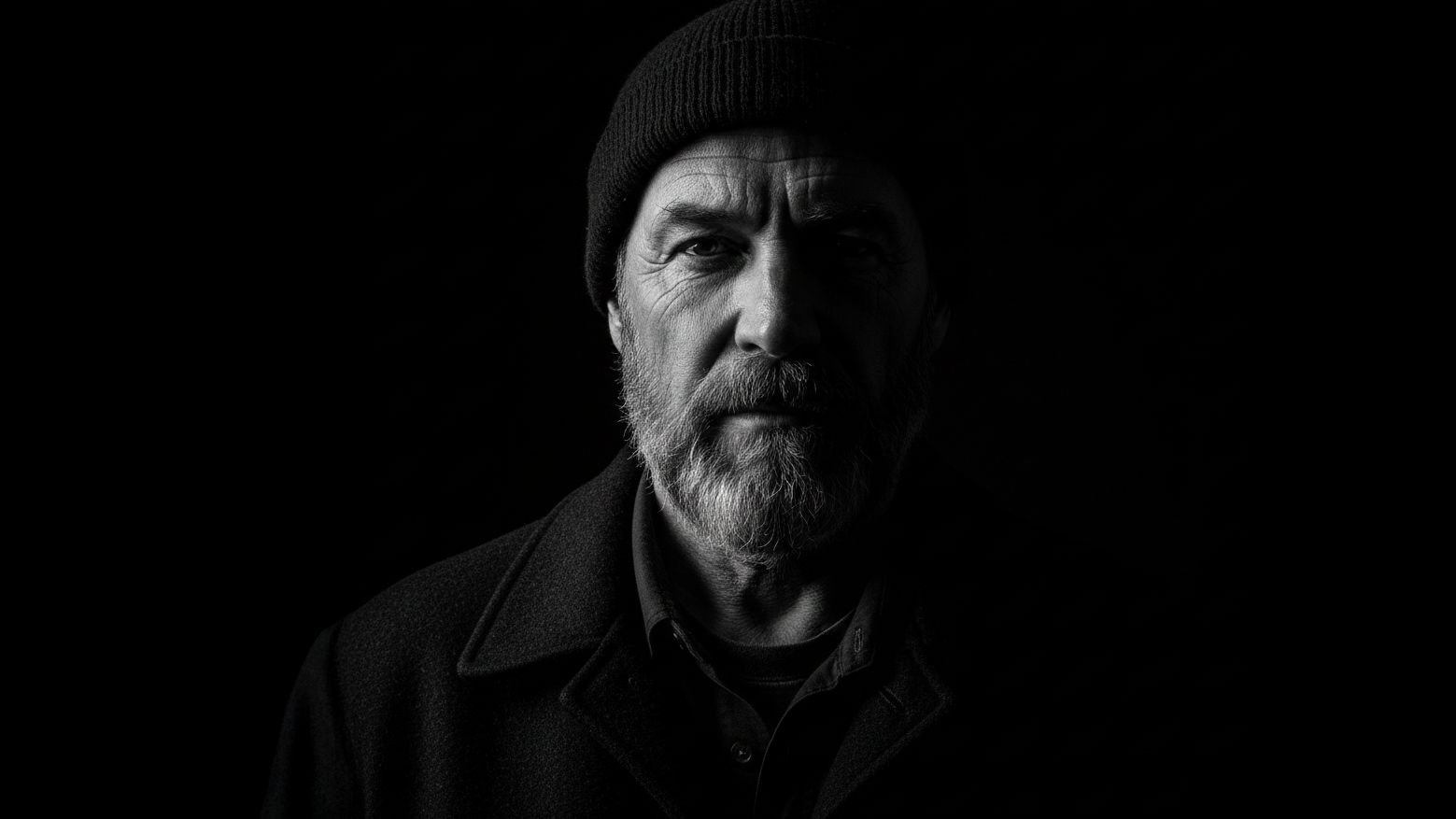

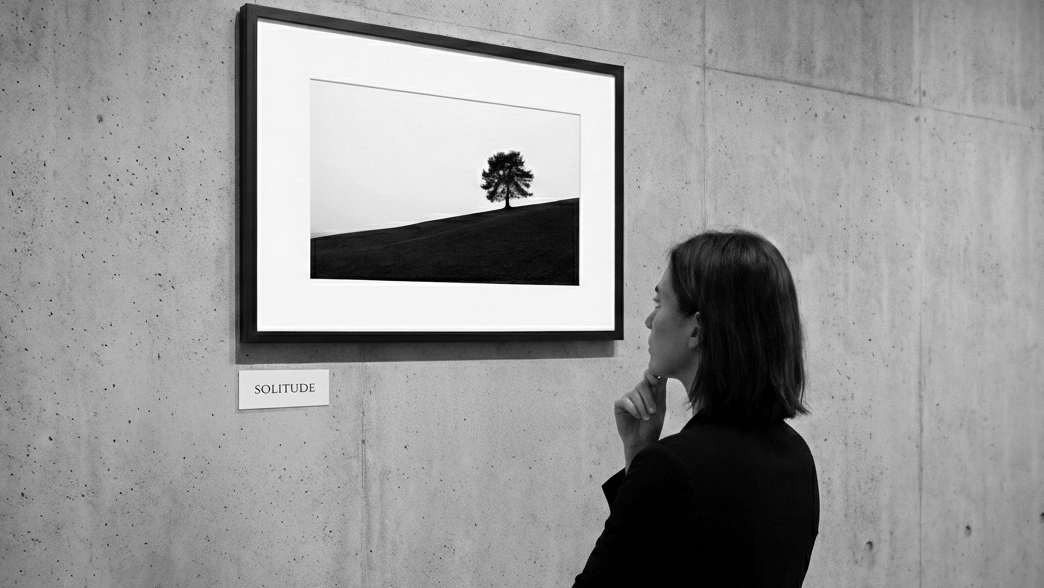

When you take a technically flawless digital file and convert it to black and white, the result is often described as "clinical," "sterile," or "flat." It lacks the tactile quality that makes classic analog photography feel so alive.

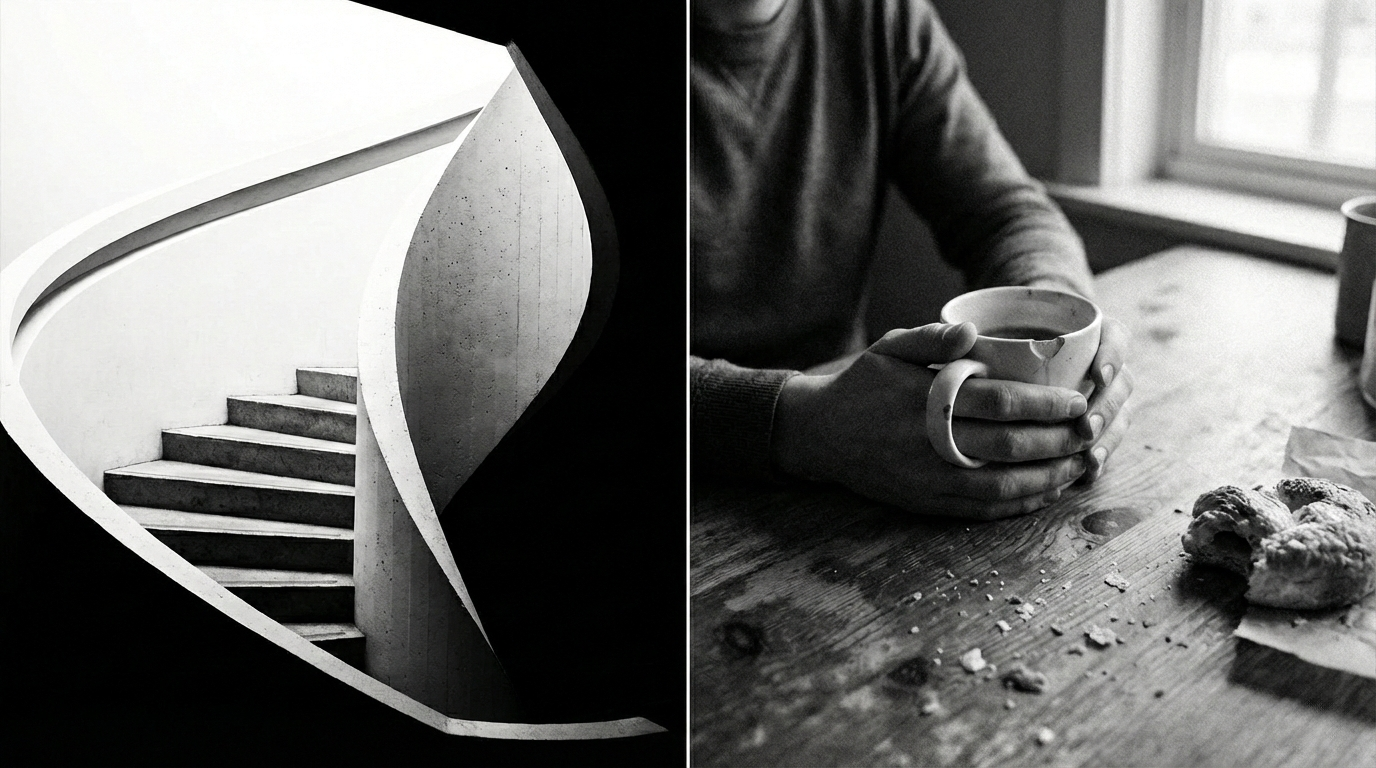

The missing ingredient is texture.

Today's Monochrome Minute is about breaking the perfect digital grid and reintroducing the beautiful, organic chaos of film grain.

The Science of Soul

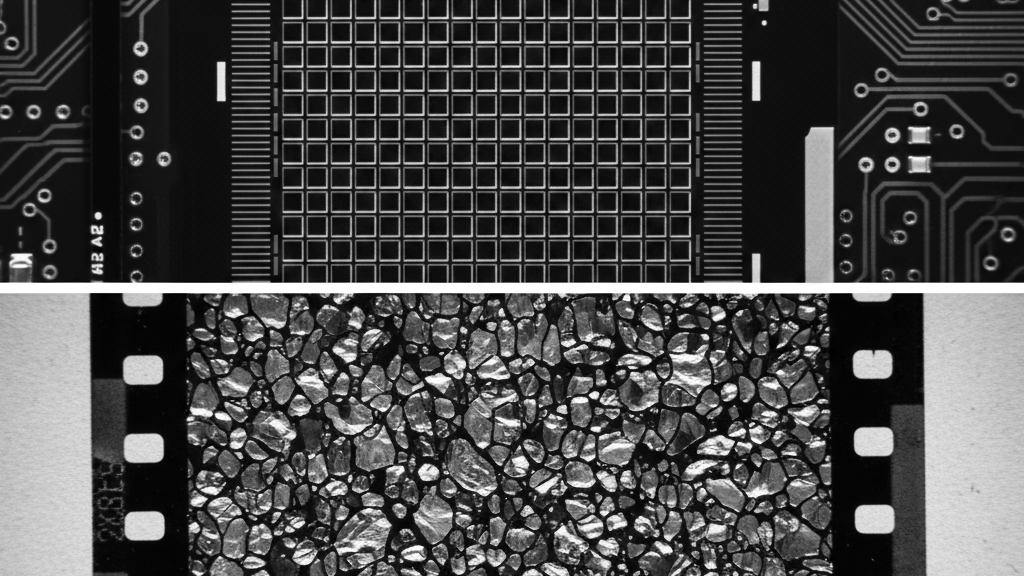

To fix the problem, we must understand it. The difference between digital noise and film grain is structural.

Digital Pixels are a Grid: A digital sensor is a perfect grid of square buckets (pixels) catching photons. Digital "noise" happens when those buckets miscount the photons, creating perfectly square, uniform artifacts of color or luminance. It looks like static.

Film Grain is Chaos: Film doesn't have pixels. It has silver halide crystals suspended in gelatin. These crystals vary in size, shape, and distribution. They clump together randomly.

When we look at a film photograph, our brains subconsciously register this organic randomness as texture and depth. When we look at a clean digital file, our brains register a flat surface.

The Goal: We aren't trying to add digital noise. We are trying to simulate analog randomness to break up the digital uniformity.

How to Add Organic Texture

Most modern editing software (Lightroom, Capture One, Silver Efex Pro) has excellent grain simulation engines. But simply cranking the "Amount" slider up won't cut it.

Here is the three step approach to crafting organic texture.

1. Size Matters

The size of the grain dictates the feeling of the image.

Fine Grain (Small Size): Mimics low ISO films (like Pan F or T-Max 100). Use this for portraits, landscapes with fine detail, or images where you want a smooth, sophisticated finish. It adds "bite" to sharpness without being distracting.

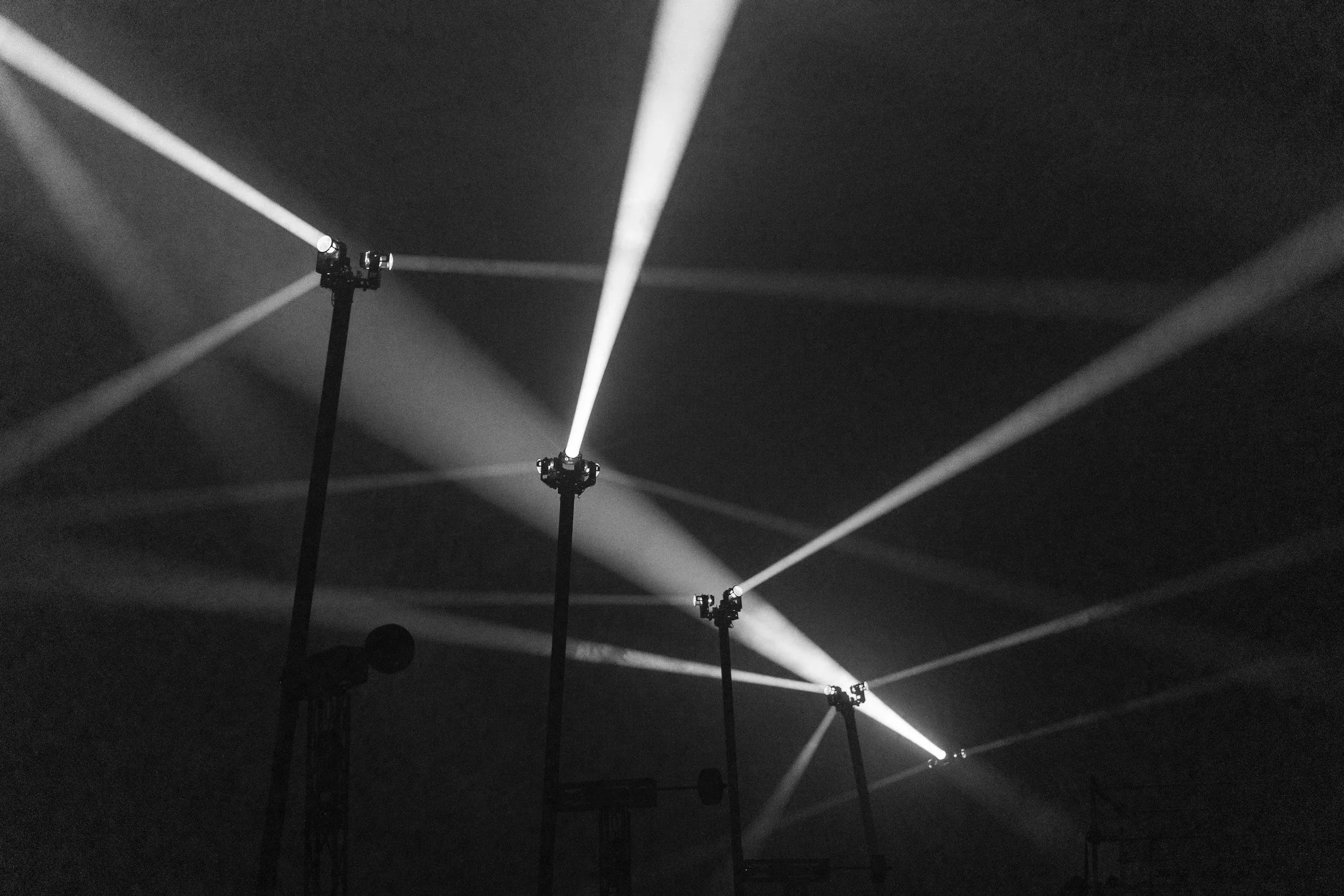

Coarse Grain (Large Size): Mimics high ISO films (like Tri-X pushed to 1600 or Delta 3200). Use this for gritty street photography, moody documentary work, or images that are already soft and atmospheric.

The Rule of Thumb: The larger the grain, the more "emotional" and raw the image feels.

2. Granularity is Key

This is the most crucial slider, often called Granularity, Roughness or Variation.

If grain is perfectly uniform in shape, it looks digital.

Real film crystals clump irregularly.

Increase the granularity slider to introduce variation in the grain structure. You want it to look like scattered sand, not a neatly printed pattern. This irregularity is what tricks the eye into seeing an organic surface.

3. Tonal Placement

Real film grain does not exist equally across the entire image.

Grain is most visible in the mid tones and shadows.

Grain tends to get blown out and disappear in pure highlights.

How to apply this: Excellent software like Capture One handles this automatically (their "Silver Rich" grains behave this way naturally). In Lightroom, ensure your grain isn't muddying your pure whites. If your highlights look dirty, back off the grain "Amount" slightly.

The Final Check

Don't judge your grain fit to screen. Zoom in to 100%.

Does it look like a layer of digital dust sitting on top of your image? Or does it feel integrated into the image, constructing the very fabric of the shadows and mid-tones?

If it’s the latter, you’ve succeeded. You’ve taken a sterile file and given it a soul.

The Takeaway

Imperfection is human. While digital cameras strive for mathematical perfection, art often strives for emotional resonance. Don't be afraid to break the flawless digital grid. A little bit of controlled chaos is often exactly what an image needed to come alive.